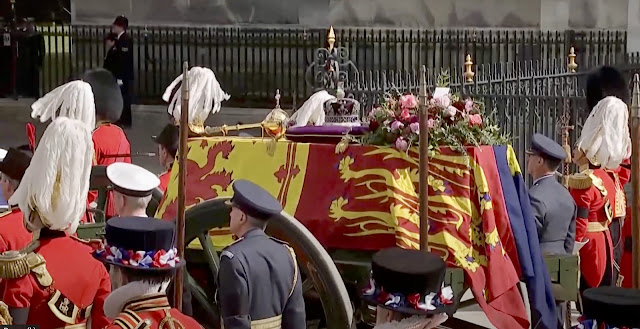

The funeral cortege presented her predicament well: her coffin was placed on a gun carriage and surmounted by the Crown. The bare fact, despite the mansions and privilege, was of a person being held in the grip of the State, complete with its military underpinning and regal cap. Whatever the nation, the emblems, we're all in the grip of that power; even though it fails to hold us together, and barely holds itself together.

So it was also impressive that she held herself together personally and ethically in that locked-in role, under the glare of media scrutiny for 70 years. That took patience, equanimity, and, above all, resolve – In Buddhist terms, the woman had some parami.

Holding it together personally takes some skill. And if you expect that look for that to happen in terms professional success and personal drive, take a look at the profile of the great and the mighty: fraud, sex scandals, violent criminality, suicides, sleaze –human minds that have lost touch with values. So it is: unless people have faith in something beyond the material world, something that connects them to the welfare of others, they lose balance and integrity. All outer, no inner.

How to integrate the outer and the inner? As one of the more renowned teachings of the Buddha (Satipatthāna sutta M:10) notes, one practices mindfulness of body, feeling, mind and its programs internally, externally and both together. The standard interpretation of those phrases 'internally, externally' is that it means 'with respect to oneself and to other people'. Which is a good idea, but the idea of watching other people and imagining what they're feeling and what their mind-states are seems impractical, and subject to misinterpretation and projection. Can I really know whether someone is actually feeling pain or bluffing? Can I with clear mindfulness witness someone else's mind as contracted or elevated?

There is another way of understanding this ‘internal/external’. In the the Sedaka sutta (S.47:19) – a sutta within the book of the satipaṭṭhāna teachings (Saṃyutta Nikāya 47) the Buddha uses the analogy of a young acrobat who is balanced on a pole that is being carried by an elder acrobat who himself is balancing on a pole. Pretty scary, eh? So the older acrobat recommends that they look out for each other. To which the younger acrobat's rejoinder is that he should look after himself and she'll look after herself and that will be the wisest way to maintain balance. The Buddha approves of this, adding that this is analogous to each individual developing and cultivating the establishments of mindfulness on body, feeling, heart-mind and its programs. So rather than be mindful of what other people are doing–, establish mindfulness on your own body. For an acrobat that takes an unwavering focus on internal qualities of energy, tension, strain, connectedness, as well as on the external contact with the pole and awareness of the body within its space.

The point is made even more directly in the following sutta, Janapadakalyāṇī Sutta S.47:20. Here it's not about balancing, but a kind of juggling. The analogy is of a man who has to carry a bowl brimming with oil on his head, through a crowd of people while the most beautiful girl in the land dances in front of him. Should he spill a drop of that oil by being distracted, a man walking behind him with drawn sword will cut off his head. Do you think he'd be mindful of anyone else's body but his own: internally – how steady and balanced it is – and externally – how it moves through that crowded space?

After all, if the Buddha meant internal = yourself, external= other people, why didn't he say so?

In the full exposition, you'll also read of mindfulness of the sense-bases internally and externally. I don't see that we're contemplating other people's eyesight. But the internal sense of seeing, that which opens when you focus on the act of seeing rather than on the seen, is one of spacious and subtle luminosity (try it in a darkened room). Auditory consciousness, when attended to, offers the 'sound of silence'; and, most important, the heart-mind of emotionally driven thinking opens to a heartful and receptive awareness.

So to most fundamentally hold us together we have the 'internal’ – the somatic vestibular 'inner' sense that the body has, and through which it maintains balance. And the ‘external’ – as the body's tactile sense through which it knows where it is in the world around it by the pressures, warmth (and so on) of the skin. You could also understand internal as the interoceptive sense (how a body knows each part in relation to the whole) and external as the proprioceptive sense (how it knows how to move through space). Try practising that. That’s what an acrobat does.

Through such mindfulness the body has a presence which is grounded, steady and able to discharge stress. It allows us to remain open without getting shredded. In this way, it supports the internal qualities of the mind. Maintain these, the Buddha says, and Mara, the force of delusion and ignorance will not get you.

However, a mind that extends externally without mindfulness is wide open to those forces. We can lose our bodies, our natural rhythms and our ability to rest and regenerate in that insistent tide of speculation, plans, media, possibilities and urgent to-do-lists. Caught in this tide, we can also lose a vital aspect of our minds: wisdom. Let me explain. The Buddha noted that the process of thinking consists of two functions – conceiving, or bringing an idea to mind (vitakka) and fully sensing and evaluating that which has been brought to mind (vicara). It's rather like the two-fold actions of a hand: the fingers grip something and roll it around in the palm and the palm fully senses and evaluates that thing.

Problem is, this takes time; a second or more of valuable time. And in the high-speed world of technology, such a mature process is a waste of time. The result is attention disorder, automatic behaviour driven by stimulation, and a deficiency in terms of the reflective thinking that will give us a reference to whether an idea is ethically sound, or what the consequences could be of acting on any specific idea. In automatic mode, conscience, concern, perspective and sensitivity are reduced or bypassed. People lose heart, get overwhelmed with uncomfortable thoughts, and obsess. In other words, if our minds are directed outwards, (as 'external' is supposed to mean) this is notnecessarily for the welfare of others. If however, our attention is directed internally, we can evaluate, reflect and come into heart. This 'internal' is therefore for the welfare of others. Because if we steady and clarify that internal base, and bring that to bear on how we speak, plan and consider our actions; that is, if we bring the internal and the external together – that will result in skilful behaviour with regard to other creatures.

This is how mindfulness internally/externally can hold body, heart and mind together. Getting into the body, using that to steady the mind ... the beautiful truth is that if one is in balance and stays whole, the mind will settle into clarity and empathy – that's the default when ignorance and stress fall away. Then, as the Buddha also teaches in the Sedaka sutta – one protects oneself by protecting others through the cultivation of patience, harmlessness, kindness, and empathy. These internal qualities emanate from a rightly balanced mind. And that finds its basis in mindfulness of body.

This is because if you bear the whole external body in mind – that is, spread your awareness over the skin boundary – you become more receptive. Skin, unlike the eyes, is not directional, it doesn't aim for anything. It receives, and refers sense-impact to its internal base – as in 'this pin-prick is unpleasant, but it's not pushing me over or a deadly threat, I can remain calm and stable as I deal with this.' A more common and useful application could be 'there is nothing squeezing or obstructing my chest or back, I have space, I am not under pressure, I can remain composed.' By so doing, we can discharge the sense of pressure of time, option paralysis and having so much to do by bringing the heart away from the flashing lights and notions of the external direction and settle it in the groundedness of the body. Steady the mind/heart internally, and, as it settles, awareness opens to the value of skilful action and empathy for others.

So this is how mindfulness internally/externally can hold us together. It has worked for millennia for those who practise it, even as empires and states have come and gone. Meanwhile in terms of the public domain: wouldn't it be good if people actually spoke straight from the heart? Rather than from the screen or the script? Wouldn't it be refreshing if public figures actually spoke truth, ''words that are useful, worth remembering, well-grounded’ rather than worn-out slogans and empty promises? That is: get out of your head, your script about who you are and how things should be, and be here, receptive, open and grounded. Give up what's not your priority. Instead regain nobility – without the headlines or the paparazzi.